In this article, we continue our series on Competitions.archi, presenting a collection of articles on different architectural competitions. Today, we will be featuring the winner of the Teach on the Beach Competition – an article from Architecture Competitions Yearbook 2023.

Firstly, the main thing to do to begin the design process was to investigate and discover the philosophy that gives support to the activities that the NGO Teach on the Beach does, try to understand it’s educational model, as well as understanding it’s motivations and objectives in a short and medium deadline. What the bases of the competition contained were a great help tool, such as the first webinar in which the director, William Agbo, commented on his experience with the NGO and his expectations for the architectural competition. Additionally, when analyzing the competition bases carefully, this allowed us to get through topics about the culture, habits, geography, and weather in Busua (Ghana), and these are some of many of the topics that we were about to get into at the beginning of the architectural design process.

We are from Cali (Colombia), a city far away from Busua, and we managed to establish a connection between the uploaded videos on social media and the specialized texts about the culture and the architecture of the place – two different ways to learn, but equally as valuable if used properly. The texts explained to us in an academic way the constructing ways and traditions that, at the end, get to be represented through architecture. On the other hand, the audiovisual material showed us ways in which people nowadays make use of them and describe those constructions through the texts. This mix of methods to learn about the place allowed us to get closer to constructive processes, to the region’s materials, to ways and styles of the local architecture. Above all, it helped us understand in a holistic way the mission and vision of the NGO and the importance of permitting the actions of foreigners volunteers thal benefit a population by making interculturality the base of their educational and social labor.

The first approach to the project was produced through a drawing that focused on something that was determining for the final proposal. It contains four basic elements (and materials) that we had to take into account for the making of the proposal and the final image of the project – this scheme shows a construction which is based in soil to level the building, a rammed earth wall, wooden pillars and thatched roof. We feel that this should be a design criteria and having this clear, we are obligated to make one of the initial proposals, no matter its shape or special distribution, as a principle the formation gathering these four elements.

The design process continued with formal explorations that contained the required program. At this point another criteria for the design appeared, which insisted on thinking of the main spaces as free circulation zones, organized, and separated in services blocks such as the bathrooms, the pantry, the kitchen, the stairs and other areas that thanks to their programmatic content are meant to be in small and closed spaces. The idea was to generate a fluid space through the most significant areas and the ones with a fuller educative content (classroom for adults, shared kitchen, and communal dining area) achieving to establish an Educative Village open to the community in general.

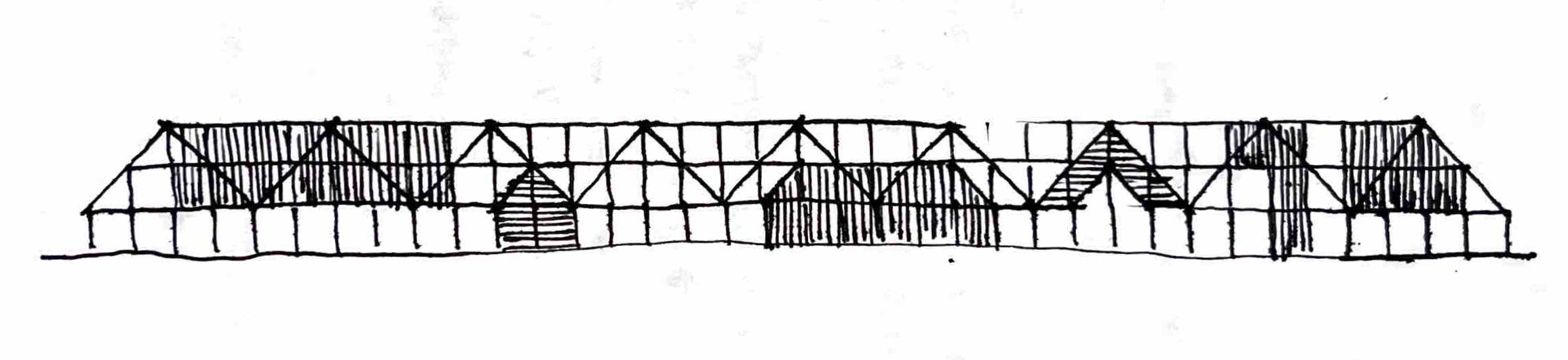

For this contest it was especially important to imagine the constructive process of the educational center and for that reason we decided to begin our design from the section with the intention to create a structural frame that would contain all the spaces from the architectural program and at the same time it would be enough to endure between the transformations in the process of designing. We imagined this frame in wood so it could be an easy structure to build within the flexible development of the project which led to the incorporation of the desired spaces and required in the competition briefing. Our architectonic idea was to create a big structure that would contain the architecture program, a big container that also would give shadow and thermal comfort. We rehearsed a scheme of the continuous building, but did not develop this way in the plot, because it did not fit, so we had to rethink the form without sacrificing the criteria that brought us here. At this point of the process, we began to alternate hand drawings with the usage of a 3d modeling software (SketchUp).

Since the plot and the initial architectonic scheme were not compatible, we began to generate different possibilities of implementation of the project. This gave us four forms of grouping in which we always had as a guide the criteria mentioned before, adding to them the necessity of forming a central space that would accomplish the function of organizing the planned scheme and that would also integrate the constructed building. These new criteria of the design permitted us to organize the proposal having into account what our idea was always the searching of the constitution of an Educative Village that could integrate any convincing form of the new and existent, and just like that is how the void space transformed into the generator of architecture and in the impulse to consolidate the formal proposal.

The first selected scheme was the one that had a ring-like shape, and it formed an inside backyard (it’s important to highlight that a similar scheme was prized with honor mentions in the competition). What did not convince us of this proposal was that it only offered one building next to another and the space between them did not have character, there was no relationship nor harmony between the existent and the new, it was hard to imagine already built by stages and its radial form complicated the functioning of some of the spaces. We tried to develop it, but it did not acquire the form we desired, and it became a problematic scheme that did not allow the fluid development of the design process. However, trying to understand how we could introduce the program on this scheme allowed us to have the parameters to design in the best way possible which then led to the final proposal.

After the analysis, we chose to use the scheme that separated the program into three blocks and starting from there we determined what could each one contain, which also helped us define the way the construction was going to take, especially since the NGO could choose what building was going to be constructed first and which ones later. Simultaneously, we continued with the idea to generate a designing structural frame which allowed a constructing facility. At this point in the design process, we started to see how the final proposal looked.

This is when we started bioclimatic analysis, a subject that bears a lot of importance in our proposal. This analysis determined the final position and orientation of the buildings, the ideal materials for the facade and the inclination of the angles in the roofs. Let’s remember that our decision was always to make use of four materials (rammed earth, wood, thatched roof and local bricks blocks) and it was clear that there was no standardization in the disposition of the same and the edifications will be the ones that will determine the use of each material – this way each building determined, specifically, its materials and solved the enclosures on the different facades. We had access to the published information of a climate monitoring station (located in the Takoradi) and with it we worked to determine the solar radiation, the average temperature of the place and the wind directions. All of this data can be used in designing tools and we were allowed to consolidate what, in an intuitive way, we had defined at the beginning regarding the materials and methods of construction.

The following step in the process was to work on consolidating the chosen scheme, which took shape in accordance with our environmental analyses and the need to strengthen the central void we set out to create. The final step in achieving the desired layout occurred when we separated the office and the living area zone from one of the buildings, thus creating a new building that brought the architectural proposal closer to the existing village. Consequently, the void transformed into two courtyards, each with distinct characteristics and purposes, and the structures were divided into an office and living area building, an adult classroom building, volunteer’s bedrooms building, and a community building that houses the communal dining area, the shared kitchen, a leisure area, and the terrace with ocean views.

Concurrently with the process of consolidating the site proposal, the structural and architectural design was developed, both being complementary and interdependent. Both architecture and structure proved to be essential elements in defining the shape and scale of the four buildings, as well as the proportions of the required spaces, all within architecture and structure proved to be essential elements in defining the shape and scale of the four buildings, as well as the proportions of the required spaces, all within different areas but within the same structural framework. Wood was chosen as the primary support material for the structure, as well as for the enclosures. Additionally, rammed earth was added as the ideal material for protection against solar radiation, brick blocks were used for internal partitions, and straw was used as roof covering.

The challenge of presenting this entire process on two sheets (as demanded by the competition) was not left to the end; on the contrary, it was a constant consideration throughout the design process. The intention was to accurately capture the concepts, ideas, and technical and architectural development of the proposal. We decided to generate specific graphics and avoid redundancy in information. For example, we chose not to include isometric diagrams since the project needed to be clear enough to be understood in the general plan, aerial assembly, renders, imaginary drawings, architectural sections, and environmental analysis sections. Only isometric diagrams were used to explain and demonstrate the structural modularity of the proposal and its ease of construction.

We initiated the design process by understanding the requirements, carefully reading the brief, and obliging ourselves to delve into aspects mentioned in them that we consider crucial. These aspects allowed us to establish a sensitive connection with the desires of those who will ultimately occupy the required and desired spaces. We always aim to go beyond what is described in the brief, which is why we conducted rigorous research on attributes that stand out and that we identify as essential for the development of the architectural proposal. Based on this, we aim to interpret the perspectives and philosophy of the project’s future user. In this way, our intention is to build a proposal based on the immaterial, as this is what ultimately gives strength to the formal proposal. In this case, the immaterial was represented by the NGO’s educational model, the local climate, and culture. Through this analysis, we tried to give meaning to every decision related to the project’s constituent parts and the final architectural form. For us, the immaterial is what gives meaning to the material.

However, we didn’t linger too long in the research and understanding process; we alternated this phase with drawings and graphic proposals that represent everything we have been conceptualizing. This combination of theory and graphic representation gives ideal content to the presentation boards and provides meaning to the information contained within them.

Teamwork is another key element in achieving the objectives set in the pursuit of first place in an architectural competition. After theorizing, it’s important that each development related to the proposal is based on the principles created during the conceptualization stage. In other words, what was previously analyzed should be reflected in the aesthetics, graphic development (diagrams, renders, drawings), structural proposal, bioclimatic analysis, architectural details, etc. This is achieved when each team member relates to the rest of the team, and everyone has a clear understanding of the central idea of the proposal to be presented. A collaborative construction of the idea is very important, which is why the presence of everyone in the initial meetings to define the basic outline is vital, so that each member is aligned with the development of the proposal and understands the path the final project has taken.

This was a collaborative effort involving 11 individuals, including architects and architecture students. They are: Gustavo Sarmiento Peñaranda (architect, team leader), Jacobo Quintana Cardona (architect specializing in bioclimatic), Luis Enrique Moreno Morales (architecture student), Camilo Alexander Pillimue Ortiz (architecture student), David Veloza Ramírez (architect), José Leonardo Martínez Arbeláez (architect), Carlos Santiago Villalobos Camacho (architect), Valentina Ramos Salcedo (architecture student), Ana Fernanda Grijalba García (architecture student), Juan Esteban Victoria Marín (architecture student), and Isabella González Payan (architect).

Authors: Gustavo Sarmiento Peñaranda, Luis Enrique Moreno Morales, Camilo Alexander Pillimue Ortiz, Jacobo Quintana Cardona from Colombia

If you would like to ready more case studies like the one above please check our annual publication

Architecture Competitions Yearbook

The post How to win architecture competition? | Teach on the Beach appeared first on Competitions.archi.